In Memory of Jan Kott (1914-2001)

David Seelow, Ph.D.©

Great novels, drama, film, dance, fine art, and games allow us unique experiences. These experiences. At their best, these experiences transcend intellectual understanding and push empathy to the limit by allowing us to inhabit reality from the inside. In this kind of artistic encounter, you go beyond role playing a person to being that person. That is what the game “This War of Mine” (2014) teaches us.

I started college as a Political Science major because I liked politics. Yes, I was young and naïve once. When I met with my assigned advisor sophomore year he asked where I wanted to go to law school. I replied I had no interest in law school (naïve but smart too). He then suggested I drop Political Science. It would be a waste of time. Why not try an English class? This randomly assigned advisor was a Full Professor of you guessed it, English. Ironically, he was an expert on John Milton, a political thinker if ever there was one. Politics, then was not a waste of time, but I inferred, could be best approached through literature not Political Science. I listened and took a literature course in “Introduction to Drama.”

The professor was small, hunched over, constantly fumbling with a pipe (you could smoke in class those days), Slavic looking to me (when I grew up Amsterdam, New York near our home had a large Polish population), speaking in a sputtered but still perfect English with a Polish accent. He talked about Sophocles and Greek tragedy. Turned out, this professor had lived a Sophoclean type tragedy in central Europe during World War II. When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939 Professor Kott as defending his homeland. Jan Kott lived the life few of us will ever experience. He was no Ivory Tower scholar; nonetheless, a scholar he was. Professor had the cosmopolitan mind of a Man of Letters, multilingual and knowledgeable in many disciplines. For me he represented both the life of the mind and the life of the active, committed citizen, a figure like Jean Paul Sartre. I became a Comparative Literature major that semester and never stopped the love and study of literature.

Professor Kott fought in the Polish underground fighting to resist the Nazi onslaught, the Shakespearean slaughter of innocents in Hitler’s the thirst for world domination. He ran from house to house, sometimes starving, often barely surviving by an Ariadne’s thread, to a hopeful glimmer that Poland would survive. However, freedom did not come to Poland until decades later when Professor Kott had left settled into U.S. citizenship and Professor of Drama. Dr. Kott lived a life of drama, but he also spent time running the streets of Paris with the founder of surrealism Andre Breton and, the founder of Dadaism, Tristan Tzara. He translated Jean Paul Sartre. That kind of company would enthrall any novice literature major.

I say all this as prelude to the game This War of Mine (2014) because only a Polish sensibility produced by a partitioned country that experienced the horrors of war and the monstrosities of Auschwitz could produce a game of such cruelty and despair. This War of Mine can be a haunting experience. Playing the game requires a strong mind, a protected hard, and a perseverance not unlike that required to survive a war. As Zacay observes, “It [the game] remains as brutal and capricious a game as its subject matter” (2014). Americans have not experienced the horror of war since our own Civil War in the 1860s. We have been protected, for the most part, from the theater of cruelty dramatically lived the last fifty years or more in places like Syria, Ethiopia, Lebanon, and the Ukraine.

In many ways This War of Mine echoes the Siege of Sarajevo. You control three civilians trapped in a brutal siege. The three are only trying to survive in a bombed out abandoned shelter. A clock ticks down the hours. Every day is the same day. You spend the daylight trying to build various items like a bed to rest in, a stove to cook on, a radio to hear news from. At night, you leave the shelter to scavenge various locations, each with their own potential rewards and risks. Every night you risk your life, but you must risk your life to live another day. Your three players have different strengths, one might be fast, another good at bargaining. You must balance the skills and needs of your little collective. At night one will scavenge, another keep watch, and the third try and sleep some. I first played Markos, Pavle and Katia, but lost Markos relatively early.

Physical exhaustion and hunger are constant, but frequently taxing of the body also necessarily taxes the mind, severely taxes the mind, as your character ruminates, “This will never end.” “There’s no point anyway.” Evan Narcisse, writing for Kotaku frankly describes the mental stress playing the game entails, “This War of Mine is the first video game where I’ve stopped playing because of how depressed it made me feel” (2014). In this sense, the game dramatizes the despair war brings on one’s psyche to such an extent the player feels a sense of despair as well. What journalist Janine di Giovanni (2016) writing about Aleppo in Syria calls, “the annihilation of spirit.”

Like many games, your characters make decisions, but in This War of Mine, players make what Jan Kott called “radical choices.” In war, every situation is extreme, and extreme situations demand radical choices. Think about the end of Hamlet, every choice is a tragic choice. In This War of Mine, you make radical choices that test whatever ethical integrity you might have left daily. Maybe a girl gets sexually assaulted as you fail to intervene, or you turn away a starving civilian. In my game play, I stole food from a helpless elderly couple begging me to leave them alone.

In game play your characters will experience unsettling emotions such as selfishness, cowardice, coldness, and cruelty along with despicable behaviors not conceivable in peace time. This brings up the question of empathy, which Narcisse sees erode over the course of the game. Here is a unique challenge for student player and teacher. If war creates the conditions where players can feel empathy for the civilian victims, then maybe that empathy can bring about changes in our attitude toward war. Great, you feel empathy for characters, but an ambivalent empathy, because though victims on one hand, they are also, at times, despicable immoral actors in war’s daily grind on the other hand.? No easy answer here. The question is worthy of a graduate seminar. However, the question brings me back to my first college mentor again.

Jan Kott did not read Shakespeare as a typical academic. He had a brilliant scholar’s mind, but unlike say, the intellectually revered Harold Bloom who interpreted Shakespeare as an academic often does- a poet whose words need close analysis. Kott, on the contrary read Shakespeare as a man of the theater, a dramaturg. After all Shakespeare wrote theatre for a popular audience and failing to see his plays as playable strikes me as very odd and off base. Kott not only read Shakespeare in terms of the stage, but also in terms of the theater of war, especially World War Two as played out across Central Europe. A participant in that war, fighting against the Nazis Kott could read Shakespeare’s histories as the dark meditation there are. In Chapter One of Professor Kott’s great Shakespeare Our Contemporary (1964), he writes about “The Kings.” In this chapter he introduces readers to what he calls the “grand mechanism” of history. The grand mechanism ran through Shakespeare’s history plays and through 1930s and 1940s Europe. That’s what made Shakespeare, in Kott’s perspective, our contemporary in the early 1960s. The grand mechanism turns the “executioner into a victim and the victim into an executioner.” As the wheel turns, roles reverse, and there are no victors. Kott fought against the Nazis, as part of Poland’s People Army, and the underground resistance in Warsaw. Eventually, Germany lost the war, but Poland did not win in 1945. Russia’s Red Army saved the day, only to delivery Poland to Joseph Stalin, another monster of history. Kott’s momentary celebration of the communist party in the mid-1940s ended as a cruel joke ending with party renunciation and his departure to the United States.

Teaching War’s Horror Story

Let’s take the three deleterious aspects of game play mentioned about in reverse order: boredom, depression, and empathy. Games are art and what we ask of games should be what we ask of other art. Samuel Beckett’s En Attendant Godot (1952) remains one of the most powerful drama in 20th century theater. Beckett stages boredom. Much of Chekhov lacks action as well. We just wait around, but we do that a lot in life. That’s one reason we play games now- to “kill time.” A world of reflection can open up in those moments, but if your only idea of play is blasting away spaceships, I suspect you don’t watch much theater or read many good stories. Even war consists of much waiting, but that waiting is tense, and fraught with meaning.

We can easily see the value of games that teach or build empathy. Empathy helps overcome prejudice and see commonality where previously players only perceived difference. We can fully value a game that raises players awareness of depression and helps other players suffering depression seek treatment. Most of us like games fully of excitement, and fast paced action. These three statements are evident to almost anyone who plays games. Why play a game that breaks down empathy you might already possess? Why play a game that produces depression? Why play a game with long stresses of boring repetitive play? This War of Mine does all three, and yet the game has immense value for players and teachers. Evan Narcisse, who stopped playing because the game made him so depressed nevertheless concludes his review with this startling statement, “It [This War of Mine] is the kind of game that could potentially change the way you watch news, treat others or cast a vote in an election.” Narcisse is right, let’s see why your students need to play this game.

Despair? Shakespeare’s tragedies are unsparing in their bleak depiction of life: Othello strangling his innocent wife, Caesar stabbed to death by his best friend, Lear holding his daughter’s lifeless corpse. Watching this kind of tragic drama is not fun, but we do it. Shakespeare has been staged more often in more languages than any playwright in history. His writing represents the pinnacle of the English language. Do I need say more?

Challenging empathy has a value as well. Do all people deserve empathy? Hitler? Stalin? Look back at history, there is a long, long, long list of merciless tyrants not to mention our everyday assortment of child abusers, animal abusers and so on. Challenging empathy brings us into stark confrontation with the dark side of humanity and to deny that is to live in pure fantasy. Not just those we can easily dismiss as evil, but all of us when put in extreme situations where survival means making impossible choices that can easily suspend our moral frameworks. A review in Metro Entertainment about the release of the game’s Nintendo Switch Complete Edition observes how the unique mechanic of remorse makes this game’s representation of empathy so powerful and transformative.

“This is the only game we can think of where remorse is used as a game mechanic, so even if you’re heartless enough not to feel bad about stealing someone else’s food the character in the game will hang their head in shame, drag their feet, and become ever more listless the more horrors they’re forced to perform. If left unchecked depression can quickly set in and that can in turn lead to suicide.”

In other words, if the game’s brutality challenges empathy for characters, the characters’ shame at acting without empathy makes you stop and evaluate empathy and the human condition. Professor Kott would call this in reference to Shakespeare as an example of life imitating art, but we all know, “All Life’s a Stage” (As You Like It, II vii).

Rethinking War Games

There are wargames and there are games about war. I reserve the problematic term “serious games” for genuine wargames. Wargames are designed for the military for use in actual military combat and strategy. They are most often used in places like the Naval War College. These games help the military plan for actual events, extreme events, where real lives, not avatars, are at risk. Games about war like the enormously popular Call of Duty series are for play. They are mostly adolescent power fantasies. First Person Shooters like COD are no doubt lots of fun for its millions of players, but these games give a skewed, and, ultimately, superficial perspective on the horrors of war. This War of Mine exists somewhere in the middle, but much closer to a genuine wargame than a game about war. War is not glamourous or heroic. Casualties are enormous and inevitable, especially for civilians caught in the crossfire of national, ethnic, or religious conflict. You don’t beat This War of Mine. You hope to last until a ceasefire. The Siege of Sarajevo, to give a reference point, went from April 5, 1992, until February 29, 1996. That’s a very long wait.

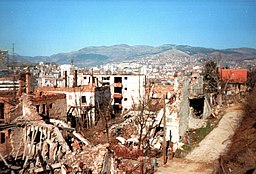

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6d/Sarajevo_Siege_II.jpg

Hedwig Klawuttke 1997

The Siege of Sarajevo is a good real world analog for This War of Mine because of the civilian catastrophe. The extended siege started with sniper fire on a Muslim wedding and civilians were targeted throughout the siege, including children (This War of Mine also has a version what includes children). The city’s central artery was known as sniper alley. Civilians were routinely shelled by artillery fire to such extent that NATO took military action (authorized February 9, 1994). In the end, over 8,000 soldiers died fighting over the Bosnian capital, but more to my point 5,434 civilians were killed for just being there, living where they considered to be there home. In terms of empathy, look at the case of Serbian commanders Radko Mladic, “The Butcher of Bosnia” and Dragomir Milosevic (U.N., 2021).1 Do such heinous monsters merit empathy? Do people who commit crimes against humanity and genocide merit anything but contempt?

These are big questions, and such historical tragedies need to be discussed and understood by students for there to be any hope of preventing such atrocities in the future. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet makes this point in summarizing the International Tribunal’s purpose, “I urge Governments and elected and public officials to strive for justice for all victims and survivors of the wars in the former Yugoslavia, to assuage – rather than aggravate – the region’s open wounds, and to foster reconciliation and long-lasting peace. Only by honestly addressing the past can a country strive to create an inclusive future and build accountable institutions for all its citizens.”

This War of Mine also has genuine value as a wargame. If all military personnel were required to play such a game and to really focus entirely on civilians in armed conflict the perception of war might be altered and the willingness to engage ethnic or nationalist differences in a military fashion might be slowed down and efforts at reconciliation extended. Our own internal struggles in the U.S. and some of the nationalist frenzy need to dissipate and the irrational celebration of guns replaced by a clear perception of innocent casualties resulting from gun fire. Encourage students to play This War of Mine. The game might help counter the simplistic power trips unleased to blockbuster games about war might help students realize that war is not an exciting hero’s journey but rather a savage journey to the heart of darkness.

Teaching History during a Time of Historical Denial

Once again, I must trot out the often repeated but never heard dictum from philosopher George Santayana, “Those who forget their history are condemned to repeat it (1905). The United States has been experiencing a time of dramatic denial. The first step in overcoming a substance use disorder (addiction) is overcoming denial and accepting the reality of your situation. We have a former President who denied the results of a free and democratic election. The Republican Party has by and large gone along with “The Big Lie” and some candidates even campaign on a lie before the American public. Censorship of books in public schools continues, and we now have the totally uncritical, uninformed debate over so called “Critical Race Theory.” First, let’s dispel this meaningless label. A theory is critical, or it is not a theory, but rather just opinionated hot air. Race theory, like feminist theory, or psychoanalytic theory, or even literary theory, takes a well thought out, reasoned, researched perspective on a subject. Feminist theory looks at events through the lens of a feminist and challenges the dominant paradigm of history and culture written from the masculine perspective. Psychoanalytic theory looks at intrapsychic phenomenon, unconscious psychodynamic factors, and such in the formation of historical actors or artistic and cultural production. Literary theory is an umbrella term for different ways to read and interpret the meaning and value of literature.

Thus, race theory, looks specifically at history through the lens of race. Rather than accept textbook history as truth, race theory looks at historical events around issues of race. Every theory must suspend judgment on the full tapestry of history, just as scientific experiments must isolate variables to conduct any worthwhile inquiry. Theory looks at one aspect of history and examines that aspect from a critical perspective that does not simply accept official or dominant versions of textbook history. In the U.S., many states now want to whitewash history and even legislate against historical truth as if propaganda is an appropriate way to teach history in an open democratic society. To deny racism or the effects of racism like the denial of the Holocaust, is to deny history, erase an entire groups experience, and perpetuate dangerous, discriminatory, and hateful versions of history that young students will quite possibly internalize and reproduce. James Joyce referred to these distorted historical perspectives favoring the privileged or conquerors vantage pint the nightmare of history.2

In the former Yugoslavia, the Serb Republic’s nationalist President Milorad Dodik has banned the teaching of the Srebrenica Massacre (Reuters, 2017). This act is a wholesale denial of history. It serves to extend and empower racist or ethnocentric versions of reality that discriminate, value and dehumanize other groups. Yes, there are different historical interpretations of events, but denying reality and pretending there is only one version, the Serbian, or on the other side the Bosnian, guarantees that ethnic hostility will continue, and that cooperation, harmony and peaceful coexistence will be impossible- a sperate but equal version of the world. This imperialist policy of imposing only one view of the world, the view of the conqueror must be challenged and overturned or the future of hostilities around the world will only intensify.

Notes

1. The Serbians atrocities have been recorded many places. On July 11, 1995, Serbs murdered 8,000 Muslims in what has become known as the Srebenica Massacre. Milosevic and Mladic were convicted of various atrocities, the first sentenced to 29 years in prison and the second to life imprisonment. Reading sections of the actual court transcript (see resources below) can have a strong impact on students.

2. In James Joyce’s epic novel Ulysses (1922) the character Stephen Dedalus claims, “history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” He makes the statement in response to a Mr. Deasey’s attempt to present history from a single perspective or single voice, one that distorts historical fact and turns history into simplistic propaganda machine supporting prejudicial, and, usually, imperialistic or oppressive points of view. Without getting into the complex question of England’s occupation of Ireland to which the passage comments, I point out how Chapter Two of Ulysses (1922)is an incredible tour de force that represents and subverts an entire range of historical distortions and denials like those we have been experiencing the last few years in the United States. Historical denial and falsification are common in authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia.

Game

This War of Mine. Developed and published by 11 bit studios, 2014. This War of Mine: The Little Ones, brings children into the game world and war zone, a daring but powerful addition.

Lesson Ideas

1. “Muslims and Jews: Faith and Hope in War Zones”

The relationship between Jews and Muslims in Sarajevo is not well known, but their interfaith cooperation with each other has been a way to overcome the atrocities of war and prejudice. Reaching way back to the 15th century Muslims helped Jews escape Spanish terror. During W.W. II, Muslims hid Jews from the Nazis and even gave them Muslim names. They also saved the Sarajevo Haggadah, a sacred text. During the 1992 siege, Jews, in turn, saved Muslims, and even provided Muslim’s refuge in a Jewish cemetery. Ask students to research similar historical examples where groups reached across faith, race or ethnicity to help others during a period of civil unrest or war. This research project gives students a positive message of hope when studying periods of historical despair.

2. “War Stories as Memory and Salvation”

Stories give people hope, provide lessons for the future, and help give voice to realities often ignored in large scale conflicts. Likewise, studying the transmission of stories from worn torn areas of the world can be invaluable in understanding its aftermath. Perhaps, more the half the surviving population of Sarajevo suffered from PTSD. Another half of the pre-war population left the country: displaced persons and refugees. Ivanna Macek’s chapter on “Memories of Sarajevo” studies the stories/memories of displaced persons Sarajevo who ended up in Sweden. Have students read this chapter and talk not only about the role of memory, but also the situation of children of survivors as in Art Spiegelman’s relationship to his Holocaust survivor father. Ask students to write a story from the perspective of a character from This War of Mine following a cease fire. What is the person’s most vivid memories and what to do they communicate about survival, siege conditions, and the human spirit?

3. “Crime and Punishment”

Ask students to read a section of the actual verdict from a adjudicated by the International Crime Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. I would suggest Section II: Evidence of the Case against Dragomir Milosevic, 12 December 2007, https://www.icty.org/en/case/dragomir_milosevic. This primary document brings this general’s atrocities to student’s awareness in a way that will jar their thinking. Discuss the importance of the tribunal and why testimony is so important to justice. You could also hold a mock trial of another historical figure who has committed crimes against humanity. This kind of activity allows rich, and memorable exploration of morality and justice.

4. “Rebuilding”

Students make some extraordinary buildings and small cites using Minecraft give them a map of Sarajevo before the siege and one of the city in ruins following the ceasefire and ask them to resident Sarajevo. This project not only presents challenges to city planning, and architecture, but history and culture. How do you restore Byzantine architecture in the 21st century? What are the effects of war on the very buildings of history and its invaluable treasures?

5. Have students listen to Ngozi Adichie’s Ted Talk “The danger of a single voice” and debate the merits of leaving out parts of history or presenting historical events from a textbook perspective in secondary education. You can make the debate international since denial and the use of history to teaching only favorable realities that erase a nation’s dark spots has been used in many countries, democracies, and dictatorships alike. This exercise would be especially valuable in Schools of Education.

Resources

Websites/Organizations/Curriculum

Holocaust and Human Behavior, Facing History

This publication from the Facing History organization is an extraordinary, indispensable, and comprehensive guide to exploring racism, anti-Semitism, biases, prejudice, morality, history and justice.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, 1993-2017.

An important international tribunal based in The Hague, Netherlands. This site provides rich primary documentation on war crimes, witnessing, justice, accountability, and humanitarian law.

Story at every corner

A personal website of a globetrotting couple that gives voice to stories of all kinds, but the blog pertaining to the Siege of Sarajevo is particularly powerful, https://storyateverycorner.com/sarajevo-under-siege/.

Articles/Essays/Talks

Adichie, Ngozi. “The danger of a single story.” Ted Talk, 7 October 2007.

A terrific talk by a Nigerian novelist discussing the importance of diversity in literature, culture, and history.

Macek, Ivvana.“Transmission and Transformation: Memories of the Siege of Sarajevo,” in Dowdall, A. and Horne, J. (eds.). Civilians Under Siege from Sarajevo to Troy, pp. 15-35. https://doi.or/10.1057/978-1-137-58532-5_2, 2018.

A study of migrants, refugees and others from Sarajevo who ended up in Sweden. The author discusses and analyzes their stories and memories of a traumatic event.