David Seelow, Ph.D.©

- This is my second article/blog on games and history. The last 2 game related blogs of the summer will be short takes on games that promote positivity.

Following a traumatic event, hatred toward “the other” can be contagious, and often turn deadly. Since 9/11 hatred against Muslims in the United States has increased dramatically (PEW Research Center, 2017). The COVID-19 pandemic has generated a torrent of hatred toward Asians in the U.S. (Campbell, 2021). This hatred manifests through abusive language, verbal, and physical assaults, some fatal. People scapegoat the targeted minority group based on a poisonous mixture of a fear, and ignorance. Since people frequently perceive and represent the other through a firmly entrenched stereotypical lens changing attitudes of adults is extremely difficult. With students, however, the possibility of challenging stereotypes and widening student’s perceptions of groups who are different remains an achievable, if urgent, goal.

Hostage to Extremity

In the Fall of 1979, I was sitting in the living room of my then Irish girlfriend’s parents’ house in Dublin. I had taken a year off from graduate studies at Columbia to study Anglo-Irish literature, explore Ireland and, of course, spend time with my favorite colleen. Sinead (all names have been changed for privacy reasons) came from a family of five. Her younger brother lived in London, the eldest sister in Herefordshire, married to a British Soldier, an older brother was married and lived south of Dublin. The second eldest sister lived nearby, and Sinead lived with her parents. At the time I was staying in Sinead’s parents’ house using the younger brother’s bedroom. I looked forward to meeting Sinead’s sister Kathleen for a Christmas Eve dinner. She was bringing her boyfriend with whom she lived, to the dinner. I was a tinge surprised that the sister was living with a man since this was a devout Irish Catholic family, but the real surprise came when Kathleen introduced her boyfriend to me. Farroukh was Muslim, but not an Arab Muslim, that too what have been a big surprise for me, seeing a Catholic woman and a Muslim man together- not a potential powder keg like the Catholic-Protestant divide of the time, but certainly an atypical romance. The real surprise turned out to be he was a Muslim from Tehran, Iran. For those younger readers, just a month before our Christmas Eve dinner, on November 4, Iranian nationals- primarily student protesters, occupied the American Embassy and took American citizens hostage. They did so in hatred of the United States for its support of the Shah Reza Pahlavi, the deposed Absolute Monarch of Iran from 1953 until that very year of my stay in Ireland, 1979. The Shah had been replaced by the exiled leader Ayatollah Khomeini who referred to the U.S. as “Satan.”

I shook his hand as he sat down next to Kathleen. Sinead’s father opened the festivities with some Irish fireworks by saying “Do you know David is American?” An invitation to combat if ever there was one. We never fought, but neither did we became friends. Rather, we accepted each other out of respect for the sisters, our mutual appreciation of education, and an awareness that our countries’ differences did not require personal enmity. Our tolerance grew out of personal contact and respectful exchange. Farrokh’s brother, Basir, on the other hand, refused to be in the same room as me. I was American, and, in his eyes, by definition, satanic. The brothers’ differing responses to me spoke to a complex Iranian response to the Shah. I genuinely had no real sense of the family’s situation vis-à-vis their homeland but relocating to Ireland suggested they may have benefited in some way from the Shah’s rule. After all, they were very prosperous, lived in one of the best sections Dublin, and had relocated to a western country. Faroukh attended the prestigious and private Trinity College. On the other hand, Basir did not attend college, followed strict Muslim rules, and strongly identified with the Ayatollah’s fundamentalist principles. Divided reactions to Iran’s complex relationship to the west.

Most citizens of the U.S. and Iran obtain their information through highly biased media’s stereotypical reductionism. Given the continued hostilities between American and Iran personal contact between citizens does not happen often. However, another way to establish a rapport and understanding of the other that transcends stereotypes is through storytelling. Video games represent one such powerful storytelling medium. In a review of 1979 Revolution: Black Friday for Kill Screen, Alex Kriss (2016) makes an honest confession about his and by extension many Americans’ understandings of Iran- or rather, lack of understanding, and the subsequent benefit the game brought to him, “The name Ayatollah Khomeini meant more to me as a reference to a joke from The Simpsons than as an actual historical figure. As an adult, I became marginally more aware of Iran’s contemporary position within Middle East quagmires and U.S. international tensions, but my understanding of its recent history grew no more sophisticated.”

Iran sporadically erupts into Americans’ consciousness like a nightmare, such as the 1979 hostage crisis (1979-1981), the Iran Contra affair (1985-1987) and most recently the nuclear weapons threat (ongoing to varying degrees of intensity since at least 1981), but our understudying of the country and its history remain as incomprehensible as most nightmares do. This is where, as Mr. Kriss suggests above, powerful stories about the other, told through the visual mediums of film, graphic novels or narrative games can be a transformative in helping change biases into greater empathy and increased understanding.

Iran through a Narrative Driven Adventure Game: The Power of Art as Understanding and Empathy

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 turned out to be a world changing event in the same way the Russian Revolution of 1917 had been. Iran was turned upside down, and the emergence of an Islamic Republic replacing the Peacock Throne of the Pahlavi dynasty with the faith based leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini forever changed Iran’s relationship to the West. Americans, unlike me, who did not have proximity to an Iranian national, they most likely saw the revolution as a rather bizarre event led by religious fanatics screaming “down with America!”1 As mentioned above, one way to help students more accurately understand the hostility of Iranians toward the U.S. as well as grasp the drama and power of the revolution is though the game, 1979 Revolution: Black Friday.2

As a historical fiction adventure game, you are thrown into the middle of actual history and see it from the inside as you play the protagonist, an Iranian student/photojournalist Reza Shirazi. As Julie Muncy notes in writing about the game for WIRED (2016), 1979’s action – the revolution proper, is told through its bookend frames. The game starts post revolution in 1980 with Reza developing photos of the life changing historical events of 1979. He has become a hardened realist. The game narrative then flashes back to pre-revolution 1978 dramatizing Reza the idealist on the streets of a nation in upheaval.

The revolutionary setting gives the story an immensely capitating and dramatic story arc. As a photojournalist who attempts to keep a journalist’s objectivity Reza struggles to stay on the sidelines, and inevitably ends up being drawn into the revolutionary situation as it grows more intense. Reza records the events of the revolution letting the player witness historical events up close. A brilliant game mechanic lets you move the camera around the screen taking pictures of the revolutionary scene on Black Friday. Black Friday refers to 8 September 1978 when 100 Iranian citizens were shot dead by the Shah’s forces in Jaleh Square, Teheran. Historians see that massacre as the tipping point when the Shah’s downfall was all but sealed, and the country turned decidedly against him.

As you snap the picture by touch screen or mouse click the photo displays historical facts giving each game event a deeper historical significance. This unique game narrative technique serves to arrest the story as you step out of dramatic, diachronic time and into the contextual or synchronic time of actual history. What you learn as you snap pictures in the street gives context to the narrative once you have completed the mission and the action resumes. The game plays as a living textbook but filtered through the lens of a protagonist who both documents history and creates it the way a creative nonfiction narrative like Norman Mailer’s Armies of the Night (1968)did for Vietnam. The in-game photos are juxtaposed with archival photos from the revolutionary period giving the game another layer of authenticity.

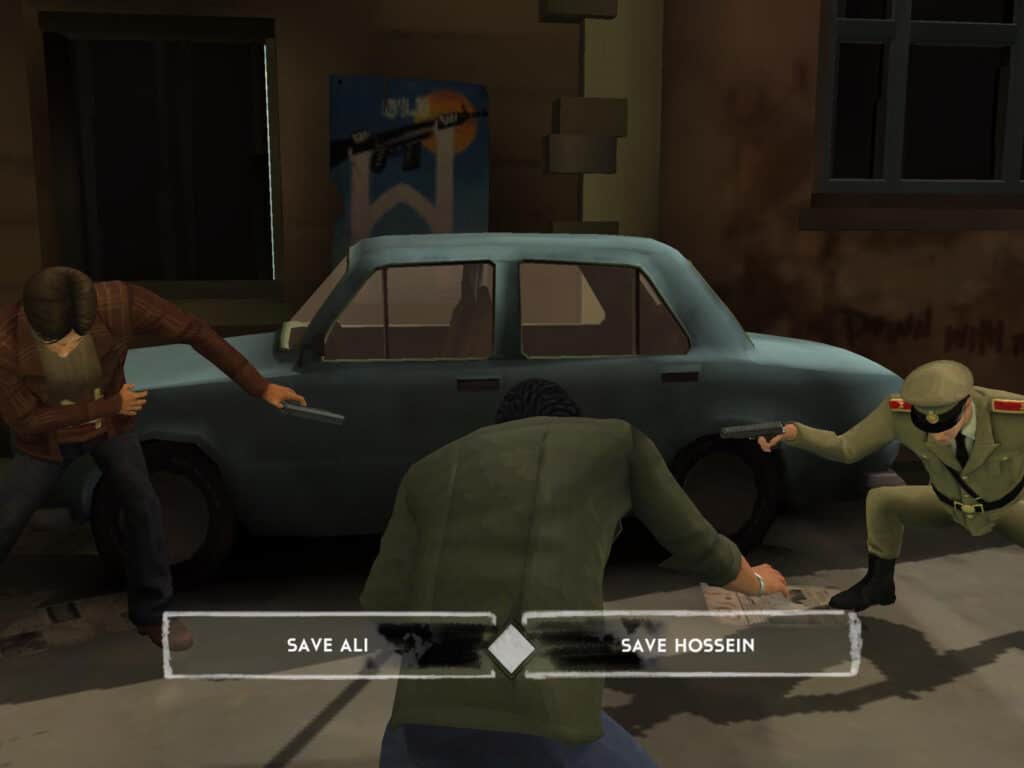

As creative nonfiction or documentary fiction the cast of characters populating the story are Reza’s brother Hossein, cousin Ali, childhood friend Babak, and the defacto group leader Bibi (women by the way played a major role in the Islamic revolution and Bibi dispels Western stereotypes of the Muslim female hidden by chador). As an adaptation of choose your own adventure or branching narratives, the adventure story works off of decision trees where your input shapes Reza’s character. Unlike more fictional games, this game’s historical context makes the decisions very authentic and almost always morally ambiguous. Every decision matter, sometimes between life and death, and has significant impact on the player. Moreover, your choice of action has a time limit. You have but seconds to make a choice. This time sensitive aspect of decision making gives them urgency and realism. When you are on the street in the middle of unrest whether to throw rocks at security forces or not must be made immediately, and yet the consequences are long term, as well as serious in both their outcome and their moral dimension. Students most likely will not have been faced with a revolution, but they will have been in tense situations- perhaps even with law enforcement- where decisions are made quickly, and consequences are profound. In this sense the game speaks to young people in a powerful fashion.

As Reza you are pulled in one direction by Cousin Ali- a provocateur who advocates the need for violence to dispel the Shah’s oppressive forces and liberate the country, and pulled in another direction by your brother Hossein, a SAVAK- one of the Shah’s deadly armed security force. This tension distinguishes the game narrative from cinema- to which the game owes much of its power- by forcing the player to make choices, awfully hard choices- tragic ones. That is the game’s essence.

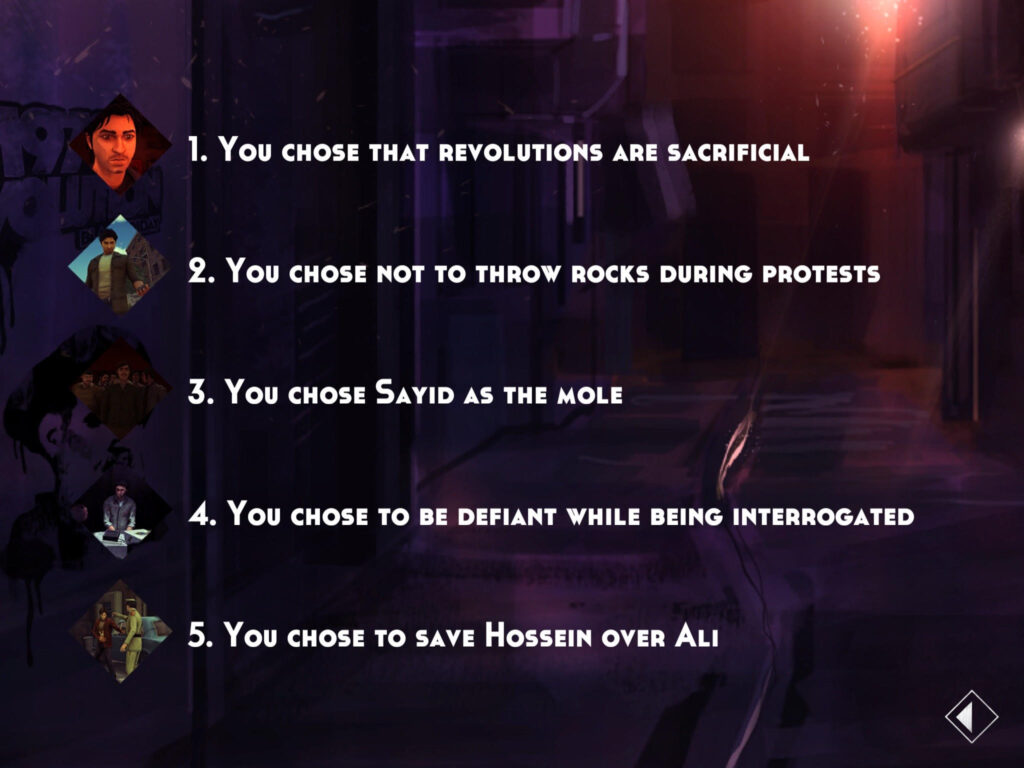

The game over screen gives the player a summary of their game play decisions. This summary would be an excellent artifact for class discussion.

In my case, the fact that I took a defiant attitude toward an interrogator and refused to throw rocks during a protest did not surprise me. These actions were congruent with my personality. My decision to choose saving Hossein over Ali proved more unsettling. Yes, I am nonviolent so Ali’s propensity for violence was off putting, but Hossein was a member of SAVAK an extremely violent group. Furthermore, he was a loyalist to the Shah’s oppressive regime something alien to how I typically see myself. I am seldom fond of the status quo. It was a quick decision, but; nonetheless, troubling to me. When do you turn your back on family? Any game that pushes you to confront your choices and reassess them has done a great job of education, whether intended or not.

Postscript

Game as History/History as Game: The Nebulous Nature of Truth and Classification

Ordinarily, I find classifying games an imperfect and even ridiculous exercise in futility, but 1979 Revolution, like its brilliant artistic progenitor Armies of the Night: History as Novel/The Novel as History (New Directions, 1968) challenges classification in a profound way that can generate rich class discussion and exploration. Norman Mailer’s text justly won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. The text describes the 1967 protest march to the Pentagon against the Vietnam War. The march was a historical fact, and the people described all historical people. At the same time, as the book’s subtitle tells us, the nonfiction history is a novel narrated in the third person by Mailer, who also participated in the march. The book also won the prestigious National Book Award, but for Art. Fiction and nonfiction at the same time, perhaps that is true of 1979 Revolution Black Friday. You can teach this ambiguity by letting students play the game 1979 Revolution and then read one or even two historical accounts of Black Friday from two different newspapers or magazines. Students will discover the events remain the same, but the meaning does not, maybe the meaning represented by the two accounts differ drastically. Is History true? Historians tell a story of facts, but facts are always mediated by language and perspective. Is 1979 a game as history or history as a game? Spend a class trying to find out and if you do let me know.

Note

1. Iranians down with America chants have deep roots and are grounded in legitimate grievance that students need to be aware of when trying to understand the nuances of history. The coup that put the Shah in power, bolstering his rule as an absolute monarch was engineered by the C.I.A. British and American strategists planned to bring down the democratic government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. It was an entirely anti-democratic action in response to Mosaddegh’s nationalization of the country’s oil reserves. In other words, Iranians wanted to control their own natural resources and British and American interests wanted to continue exploiting another country’s resources. This antidemocratic initiative was decided by two revered national leaders, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and President Eisenhour, respectively. Making students aware of this less savory aspect of American policy will give students a context for understanding the anti-American sentiments of the Iranian people and hopefully dispel stereotypes of the Middle Easterner as fanatic. We need balanced and accurate history if we are to overcome the polarized, biased thinking that perpetuates hostility.

2. The game’s title provides a stimulating juxtaposition for American students to ponder. Opposition to the Shah often focused on his imperialist connections to Britain and the U.S. with their capitalist lifestyles, and economies, which many Iranians perceived as decadent and immoral. In this context, America’s Black Friday symbolizes consumerism at its most brazen. Black Friday is the day after Thanksgiving- the official beginning of holiday shopping in the U.S. where citizens might line up and wait all night for a big sale on desired merchandise-a real evisceration of the holiday season’s deeper spiritual message. Chanukah and Christmas reduced to tablets and tv. There is something unsettling about such consumerism that makes the fundamentalist aspect of the Iranian citizens revolt a relevant criticism of Western decadence. At the same time, as the revolution passes, Reza loses his idealism. Change can be harsh, and one kind of oppression can often result in another kind of oppression. Revolution, like most of history, has a fundamental moral ambiguity, a dark grey cloud that makes the sun’s appearance too fleeting.

Game

Lesson Idea

I would take any of the exercises or activities in the Brown University Choices packet listed below and pair that activity and its historical context with the game, especially the role playing activity.

Resources

1. “Why did Iran become an Islamic republic in 1979?” Fourth edition, July 2019.

The Choices Program. Brown University.

A truly excellent history resource on the 1979 revolution with timelines, videos, background information, maps, and primary documents along with a full curriculum including graphic organizers, activities, role plays, and lessons.

2. Orientalism by Edward W. Said. (Pantheon Books, 1978). Published during the Iranian turmoil this book should be a must read for any faculty member interested in understanding how the West has historically perceived and represented Middle Eastern societies as inferior, backward, violent, despotic, and irrational. Although controversial, as most thought provoking works are, Said’s text pioneered the field of Post-Colonial Studies and opened Western thinkers and historians to the imperial nature of its devaluation of the East. Professor Said was one of my professors at Columbia. I admired his convictions, his public role, and his immense erudition. Said was a true Man of Letters in the classic European tradition.

3. Persepolis, Volume I: The Story of a Childhood (Pantheon Graphic Library, 2000) and Persepolis, Volume II: The Story of a Return (Pantheon Graphic Library, 2002) by Marjane Satrapi, originally published in France by L’Association 2000 and 2002 respectively.

This award winning graphic memoir tells of Marjane’s experience as a child at the time of the Iranian Revolution. It is a child’s perspective from the adult Marjane’s memory. In other words, you have a dual consciousness representing the revolution from a female perspective and like 1979, you have complex points of view and reactions to the events of 1979. The second volume begins with Marjane’s exile as an adolescent. The story is well established in public schools and used as early as 7th grade but should be paired as suggested above with authentic historical documents. The graphic format compares well with 1979 which also uses a graphic novel style of storytelling.

4. Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi (Random House, Reiss

Another memoir about living in Iran during the revolution, but this time entirely from an adult perspective. Nafisi also went into exile, but as an adult, whereas Marjane was sent to Vienna by her parents. This book is only appropriate for higher education. Like Persepolis, you can use the autobiographical female perspective of the revolution as a comparison with Reza’s male perspective, which given the character is filtered through another Iranian native, the game’s designer Navid Khonsari, who was ten at the time of the revolution, tells an authentic, lived experience of revolution that place in relationship to the Brown University material on women’s role during the revolution makes for very deep thinking about a world changing event from the eyes of Middle Eastern natives living in the West.

Works Cited

Campbell, Josh. “Anti-Asian hate crime surged in early 2021, study says.” CNN, May 5, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/05/us/anti-asian-hate-crimes-study/index.html.

Kish, Katayoun. “Assaults against Muslims in U.S. surpass 2001 level.” PEW Research Center, November 15, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/15/assaults-against-muslims-in-u-s-surpass-2001-level/

Kriss, Alexander. “1979 Revolution is a History Lesson for the Netflix Generation,” Kill Screen, April 20, 2016, Retrieved from https://killscreen.com/previously/articles/1979-revolution-is-a-history-lesson-for-the-netflix-generation/

Muncy, Julie. “1979 Revolution: Black Friday: Gripping Adventure Game Puts you in the Iranian Revolution. WIRED. 6/17/2016. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2016/06/1979-revolution-black-friday/.